Inside the World’s Largest COVID-19 Information Campaign

How we built a global coalition that brought public health information to two billion people and what it revealed about the deep inequities of our information ecosystem.

In the spring of 2020, as the world was shutting down for what was then an unknown and frightening virus, Meta came under intense scrutiny for the volume and speed of COVID-19 misinformation spreading across Facebook and Instagram. Conspiracy theories, as well as general falsehoods about the virus’ origins and vaccine safety were overwhelming people’s feeds and spreading confusion.

At the same time, Meta was rolling out a series of emergency measures, such as enhanced fact-checking support and prominent COVID-19 info centers within people’s feeds. And Mark Zuckerberg publicly committed to giving the World Health Organization (WHO) ‘as many free ads as they need’ to amplify public health messaging.

I had just launched Meta’s first national media literacy initiative in the US, and was also overseeing its corporate ads donations program. Misinformation programming was becoming my beat, and it was an honor to be asked to help design and deliver on Mark’s commitment.

Our first decision was to expand the program beyond the WHO to include government health authorities. COVID-19 was a global pandemic, but the response was fundamentally local. Each country had its own guidance and priorities, from lockdowns and curfews to mask mandates and toilet paper rationing. So a single global messenger wouldn’t suffice. Citizens needed to hear from their local leaders as well.

Our next decision was what kind of support would actually be helpful. Mark’s original offer of free ads was straightforward and strictly budgetary. Think of it as Meta buying gift cards that the WHO could then use to buy ads on Facebook and Instagram.

But very quickly, we realized that focusing solely on media buy would ignore deeper capacity constraints and structural challenges. Many health agencies had never run public information campaigns on social media, and needed help creating Facebook accounts. Others needed translation support – consider that India has 22 official languages, or even a country like Germany has large populations relying on Turkish, Russian, or Arabic – and that minority language speakers are often the most vulnerable to false information.

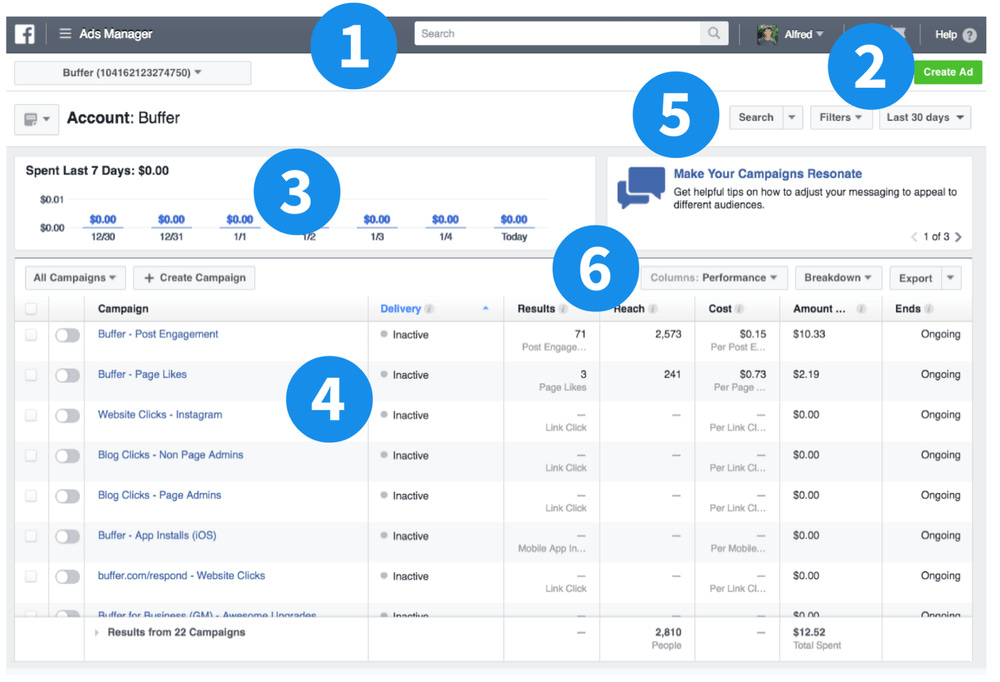

Even when health agencies had content to share, they often lacked experience using Meta’s Ads Manager to actually set up their campaigns. It makes sense – public health experts are usually focused on science and policy, rather than the latest marketing tools. And let’s face it: Meta’s Ads Manager is not beginner-friendly.

So we evolved the program further. What began as a simple ads donation program to the WHO quickly expanded to include external creative and translation services, plus white-glove, in-house support for account setup, distribution, and measurement for government authorities, UN agencies, and NGOs across 180 countries.

The program ran for three years. By the end, our global coalition reached over two billion people with authoritative health information and measurably increased public interest and perceived safety of the COVID-19 vaccine across all regions.

Cross-sector partnerships are often called for in moments of crisis, but they’re rarely described with operational clarity. And no one has spoken publicly about this particular effort with any detail.

Until now. Here’s how we did it.

Step 1: Make the content

There’s a lot of hype about video today, but even in 2020, video was already the strongest format for engagement. The problem was that very few public service institutions had the capacity or resources to produce it. We were already in lockdown, so organizing professional shoots wasn’t possible. And the kind of stripped-down, phone-shot videos we all know today weren’t yet mainstream enough to make them feel like viable options for government officials or health providers working on the frontlines of the crisis.

So our guidance to agencies defaulted to animations and infographics. It was an improvement over static posts, but still not optimized for a public that was already shifting its trust from authority to relatability.

Second, Meta’s ads system is rigid in a lot of ways – it’s not the free-for-all many assume it is. The company enforces a set of quality rules that advertisers must follow. When we started the program, for example, Meta enforced a 20% rule for text on ads — images with over 20% text were auto-rejected. The rule no longer exists, but text-heavy images are still considered low-quality content which may impact their distribution. The guideline preserves a visual-first feed, but wasn’t feasible for our campaigns which had to be largely text-based due to our production limitations.

In addition, Meta imposes strict spending caps for first-time advertisers — the majority of our program partners — until they establish a track record. It’s a fraud prevention mechanism that makes sense for most cases, but adds unnecessary friction for a time-critical campaign funded by Meta itself.

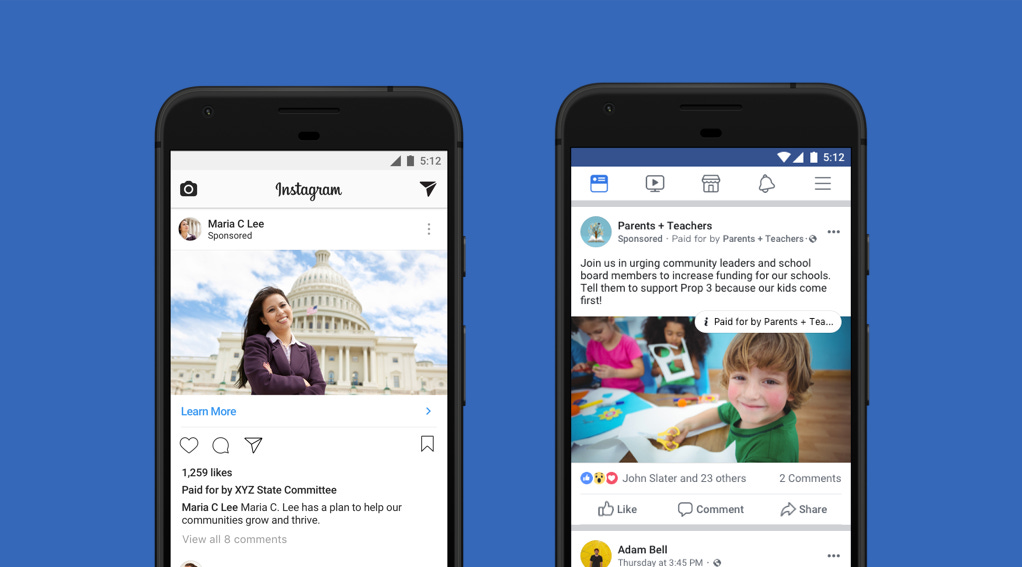

The most complicated challenge, though, was Meta’s social issues, elections, and political ads policy– which was actually one of my remits while I worked at the company. Introduced after the 2016 US election, it’s meant to address the risk of foreign interference in elections. The policy requires a ‘paid for by’ label on ads discussing politics, elections or social issues – which include health. It also requires advertisers to prove they reside in the same country where they are running these ads.

In an American context, the residence requirement is workable. But globally, it creates a myriad of operational barriers. In Europe, for example, it’s completely normal for an organization based in, say, Belgium or Austria to serve some or all 27 EU member states. Under Meta’s policy, though, they couldn’t.1

For the 20% rule and spending cap, our team had to secure exceptions for each agency participating in our program. We also successfully advocated to change the ads policy for the pandemic. Public health messaging about preventive measures, how vaccines work, or how to access them would not be subject to the same requirements as political ads.

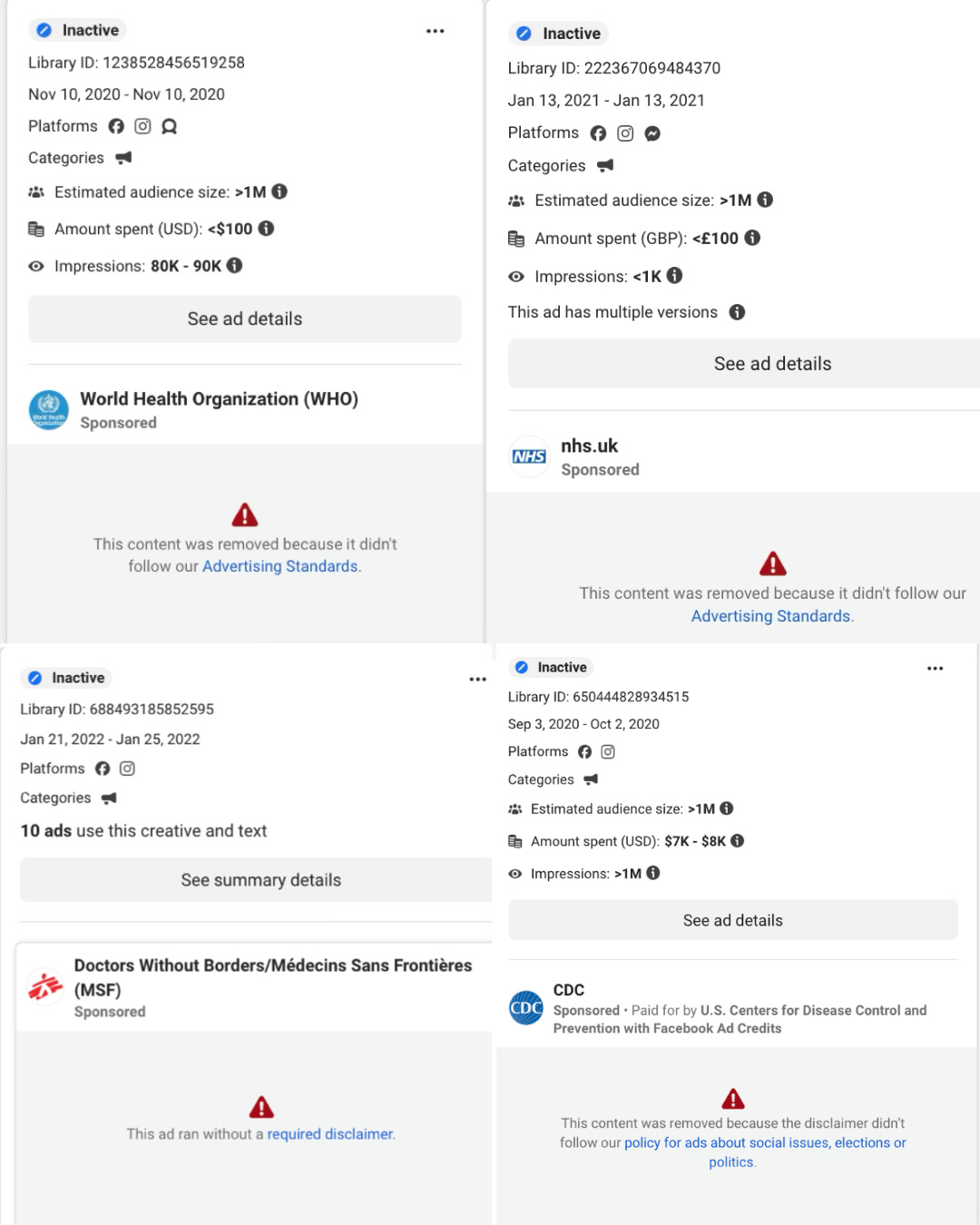

I suspect this is why many of our campaigns are no longer visible in Meta’s Ad Library. While writing this piece, I went back to pull examples from our partners like the WHO, UK National Health Service (NHS), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), or the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC). But they’re not there anymore – taken down, per Meta, for violating their ads policies.

It’s true that the ads didn’t meet the requirements. But that’s because the requirements were not designed for urgent public information needs like this.

Step 2: Distribute the content

My colleagues at Meta were incredible resources of knowledge about what makes an ad campaign successful. Besides content strategy, one of the first things they taught me was the standard cadence for an effective campaign: deliver an ad to the same person two times per week for four weeks.

That’s the general best practice for brands — the frequency most likely to drive a conversion, or in other words, for someone to take your desired action. Exceeding that risks audience fatigue, which can actually have the opposite effect and decrease interest.

So we calibrated our campaigns to those best practices. In Meta’s Ads Manager, the maximum setting per country was roughly 80% of its reachable users on Facebook and Instagram. We set campaigns to reach that maximum, with two impressions per person each week, for four weeks.

And it worked.

By late 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccines were pending approval and we helped the WHO run a global campaign explaining how vaccines are developed and vetted – with the goal of strengthening public confidence before the rollout began. After four weeks, our teams saw statistically significant increases in public interest in and perceived safety of the vaccine across every region.

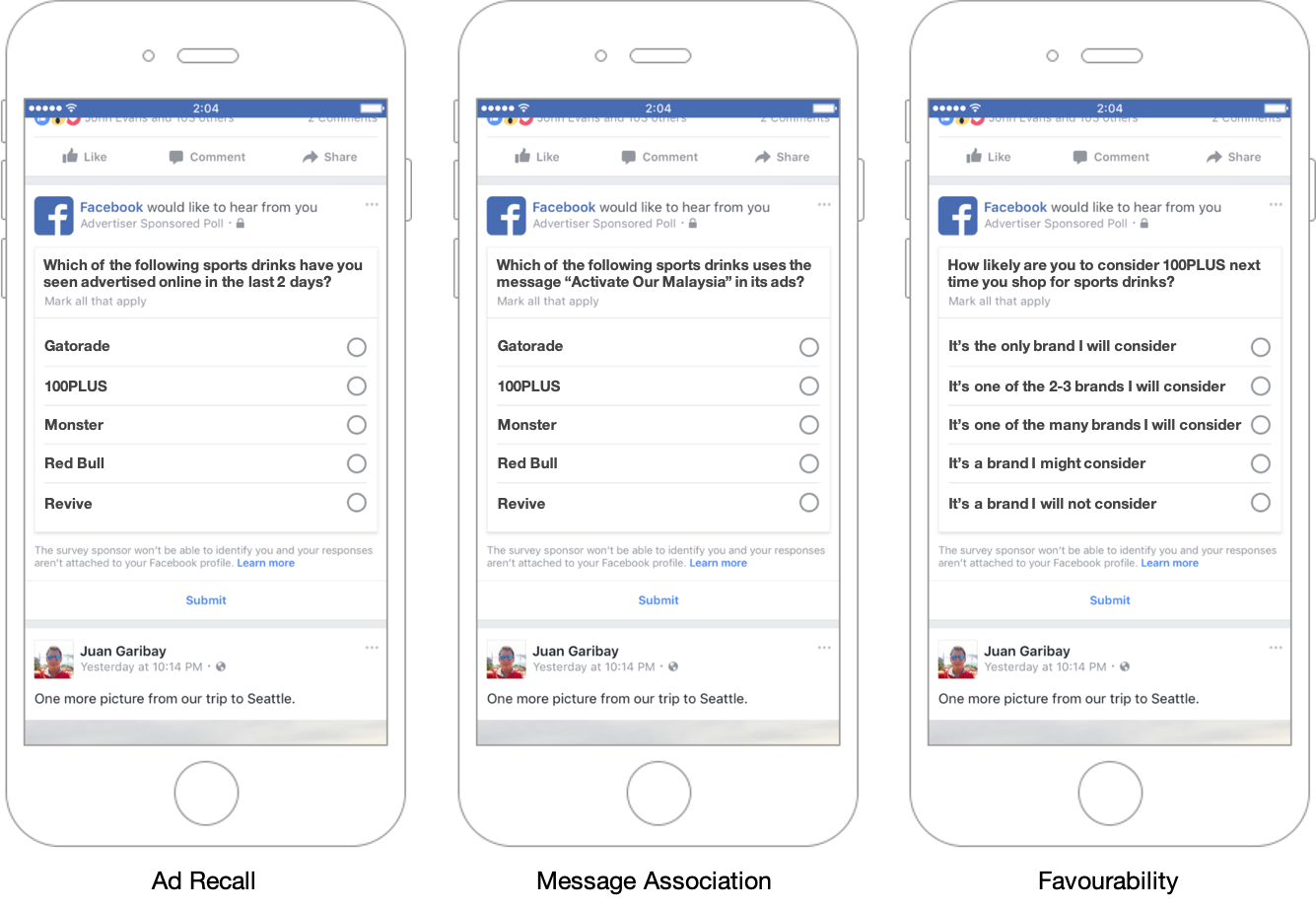

A necessary disclaimer, though. Facebook and Instagram are incredible advertising platforms, but as I’ve mentioned, they are fundamentally designed for corporate marketing and sales conversion – not public sentiment or behavior analysis. We repurposed Meta’s brand lift tools – meant for measuring consumer affinity – to capture people’s self-reported changes in vaccine confidence, institutional trust, and media literacy skills. It wasn’t perfect, but it was the best available option.

More sophisticated measurement could have provided a clearer picture of how people actually navigated COVID-19 discourse in their feeds – but in the interest of user privacy, it was not pursued.

Equity was our north star

Over three years, our program cost Meta more than $300 million. We were fortunate to do this work at an organization that could fund the actual cost of delivering authoritative health information without cutting corners. It was a privilege, and also an exercise in fiscal responsibility and ethics from the start.

Our driving principle was simple: information is aid.2 Uneven access to quality information makes structurally marginalized communities even more vulnerable. In a pandemic, that vulnerability becomes a matter of life or death.

Our program allocated resources based on the actual cost of running campaigns in each country. Meta’s ads system is an auction: the more competition for an audience, the higher the price of reaching them. That means the cost of delivering the same campaign – with the same parameters and objectives – varies dramatically across countries, depending on how many advertisers are targeting them. And what this exposes is the information inequity that is ingrained in our world.

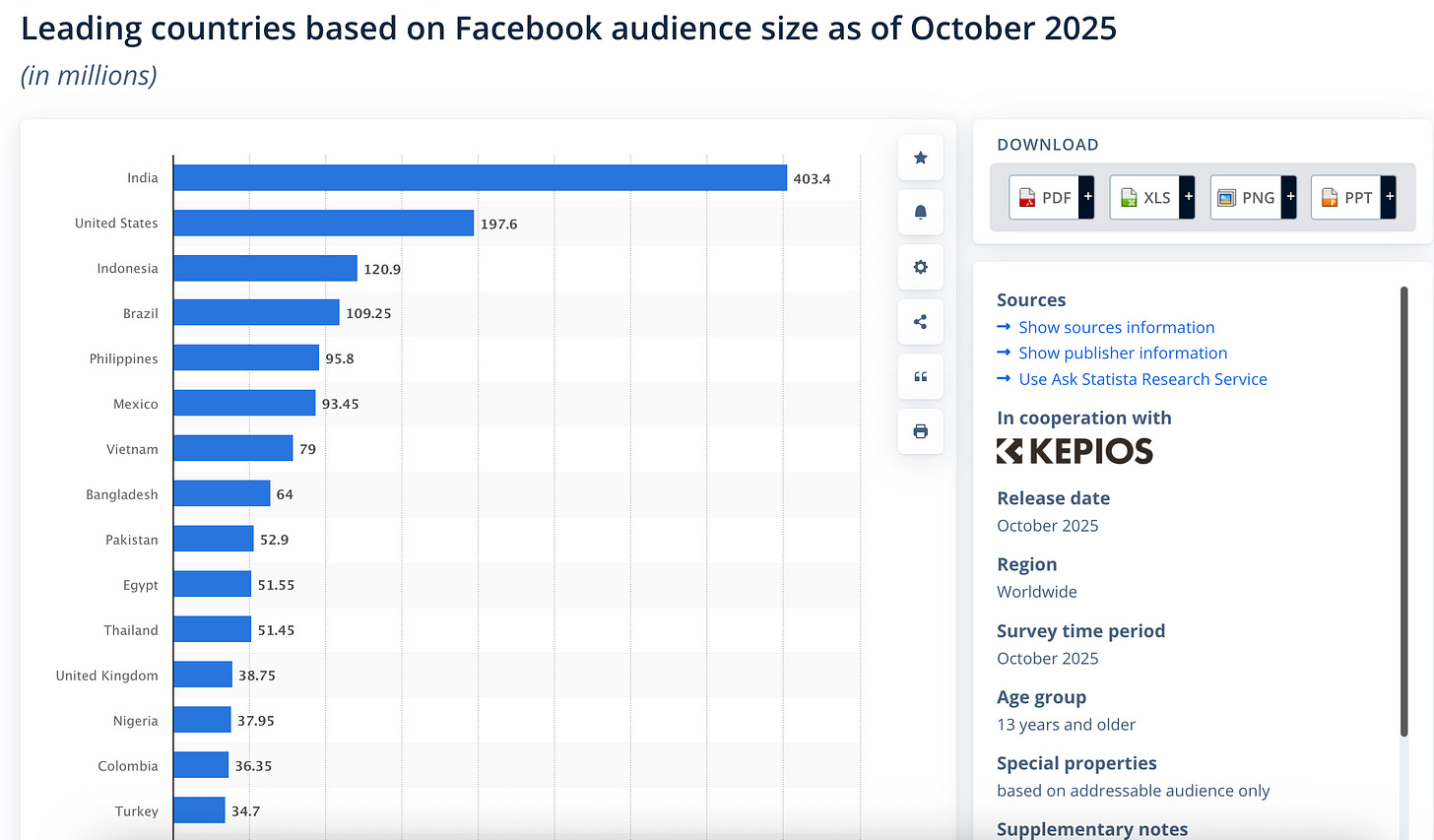

To put this into perspective: reaching people in the United States was dramatically more expensive than reaching people in India — despite India having nearly double its number of Facebook users. A similar dynamic was true across the African Union, where we could reach hundreds of millions of people across 55 countries for a fraction of the cost of a single US campaign. In fact, we could reach the whole world for roughly the same cost as running a campaign in the US alone.3

This doesn’t just show how crowded the US digital ecosystem is. It illustrates how much more information and content flows toward American audiences, even though it is far more financially feasible to reach people in every other part of the world. In fact, nationwide campaigns could be run in a number of countries — from Central Asia to sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean and even parts of Europe — for a few thousand dollars.

And in many of these places, the absence of institutional communication has real consequences. Many countries received the COVID-19 vaccine later than the so-called Global North. Maintaining trust, reinforcing safety guidance, and mitigating people’s frustration all required sustained public communication. But these were also the places most prone to information gaps.

That’s why local capacity building is so critical. As the pandemic taught us, global systems are optimized for scale – not depth or nuance. And focusing on scale alone guarantees that many communities will be missed.

Relatedly, we need to acknowledge that government messengers are not always the right ones. As the crisis wore on, COVID-19 responses became politicized, especially as shutdowns impacted trade and commercial activity.

In a handful of cases, a government partner would ask to use our program to promote official messaging that encouraged in-person activity or celebrated their own response successes, rather focusing on health guidance. Even then, our principles applied: our program was for centering COVID-19 public health.

When governments weren’t the appropriate messengers – either because their message didn’t align, or because they could not credibly reach vulnerable populations – we partnered with NGOs to fill the gaps. Organizations like AARP and AGE Platform Europe for older adults; International Medical Corps and Médecins Sans Frontières for displaced or vulnerable communities; and the National Congress of American Indians for Indigenous populations were essential. They helped ensure that people who might distrust or be overlooked by government channels still received accurate, actionable information from sources that specifically served them.

By the end of 2023, our program had reached over two billion people in 180 countries. Hundreds of government agencies and NGOs had received critical support and new capacity to use social media for public information campaigns. And people’s interest in the COVID-19 vaccine grew, as did their ability to identify potential misinformation.

Though Meta has undergone many changes since then, this infrastructure remains as a model for acute crisis response and information threats – deployed again and again in moments like the conflict in Ukraine, elections in Kenya, and wildfires in Los Angeles.

Aftermath and looking ahead

In 2024, Mark Zuckerberg apologized for Meta’s COVID-related content decisions and suggested they were made due to pressure from the Biden Administration.

That was not my experience. My reality was that hundreds of people across Meta’s policy, product, content review, legal, and partner support teams took very seriously our responsibility of stewarding the world’s largest public square during one of the most frightening periods of our lifetimes. Maybe that’s something Mark regrets now, but I don’t.

What this experience taught me is that it is 100% possible to build cross-sector coalitions, close information gaps, and meet people where they are. Removing misinformation only works if high-quality content emerges to fill the void – but that can’t happen if it’s not there to begin with. And news organizations can’t bear this burden alone, as their industry undergoes its own upheaval.

Institutions and subject matter experts need better support to participate in today’s information ecosystem. The good news is that this is far less expensive and more accessible today than it was in 2020. And we don’t need a tech behemoth to drive this work.

As the digital ecosystem shifts into its next era, now is the moment to organize experts across institutions, sectors, and geographies — not just to respond to the next crisis, but to build the information resilience we need for the future. ▪️

I help institutions and subject matter experts participate online with confidence and integrity. If you or your organization are grappling with navigating the information ecosystem, I’d love to help.

In October 2025, Meta ceased running political, electoral, and social issue ads altogether in the EU, in response to the EU’s Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising (TTPA) regulation.

Estimates are directional from my time on this program, and are intended to illustrate relative scale. They do not provide exact figures and do not necessarily reflect current auction dynamics.

"Maybe that’s something Mark regrets now, but I don’t."

Please start regretting it.

Have you ever read the covid case definition? It is nonsense. There is a serious disconnection. A case does not and cannot represent an infection. All notions of cases representing infections were misinformation. Then they removed symptoms from the case definition in 2023. The official position is that no one knows if covid has symptoms or not. And you are patting yourself on the back for manipulating people into believing and fearing it, patting yourself on the back for stopping true information from reaching their ears.

It is monstrous what you did.

Repent.

Face the truth.

Stop hurting people.

Covid has no valid definition. It is a hoax.